Book Appointment Now

Microbiome: The Secret Universe inside you

The Hidden City Within

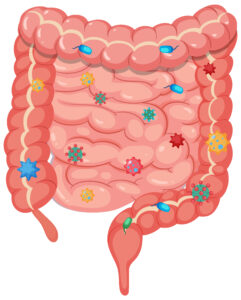

If you could shrink yourself down to the size of a dust particle and journey into your own body, the first thing you’d notice is the quiet. The second thing? The bustling city that lies hidden inside your gut — a city so vast and so alive that it dwarfs every metropolis humans have ever built.

This is the microbiome.

A shifting, shimmering world of trillions of tiny inhabitants: bacteria in countless shapes, elegant spiraling archaea, fungi weaving their delicate threads, and even viruses that dart between them like messengers. They live on the winding streets of your intestines, forming neighborhoods, alliances, trading routes, and diplomatic relations that would make a United Nations ambassador dizzy.

Most of the time, you never notice them.

But they notice everything.

They notice what you eat.

They notice how much you sleep.

They notice when you’re stressed, when you’re traveling, when you’re thriving, when you’re unraveling.

Their world bends in response to yours.

And here’s the remarkable part: your health is the reflection of this inner world.

The Symphony of Diversity

In a well-balanced gut, diversity is the heartbeat of the city.

Think of it like a rainforest — dense, layered, full of different species each playing a role. The more variety there is, the stronger the ecosystem becomes. It withstands storms, adapts to change, and bounces back from disruption.

Your microbiome works the same way.

When it’s diverse, you feel it:

- digestion is smooth,

- your metabolism is flexible,

- inflammation stays quiet,

- your mood feels more even,

- your energy lifts.

But when diversity shrinks — when monocultures begin to take over like weeds — the city becomes fragile. Problems creep in. Digestion falters. Inflammation stirs. The immune system becomes restless. Even the mind becomes clouded with fatigue or anxiety.

The Forces That Shape the Inner World

Your microbiome is not fixed.

It’s a responsive, living community — more like a garden than a machine.

And like any garden, it grows according to how you care for it.

Your diet is the daily weather. Fibers, colorful plants, fermented foods — these are sunshine and rain. Ultra-processed foods and sugar? A drought.

Antibiotics are both heroes and earthquakes: necessary at times, but powerful enough to reshape the terrain for months.

Stress and sleep are the seasons. Chronic stress is a long winter; good sleep is spring.

Childhood experiences lay the foundation of the city: the way you were born, the first foods you ate, the microbes you met early on.

Movement — even gentle movement — acts like fresh air drifting through, helping the whole ecosystem thrive.

A Living Story Inside You

When you zoom back out to your full size, you may never feel these tiny citizens moving within you — but they write your story more than you know.

They whisper to your immune system.

They send messages to your brain.

They help decide your mood, your cravings, your energy, your resilience.

Your microbiome is not just a scientific concept.

It is a companion, a silent partner in your life, adapting with you, responding to you, rooting for you when you nourish it.

And perhaps the most magical truth is this:

When you take care of them, they take care of you — in ways you can feel, and in ways you’ll never see.

How the Western Diet Damages the Microbiome

The modern Western-style diet—high in refined sugars, processed carbohydrates, saturated fats, additives, and low in fiber—significantly disrupts gut microbial balance.

Refined sugars and additives feed opportunistic, inflammatory bacterial species. Chronic consumption encourages dysbiosis, reduces diversity, and promotes metabolic inflammation.

Fiber deficiency is one of the most important drivers of microbial decline. Beneficial gut bacteria rely on various fibers to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which maintain gut lining integrity and regulate the immune system. Without fibers, these microbes starve, shrink in number, and weaken the gut barrier.

Inflammatory food patterns, such as high omega-6 industrial oils, highly processed foods, and emulsifiers, contribute to increased intestinal permeability—often referred to as “leaky gut.” This allows inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream and impact immune and brain function.

Overall, the Western lifestyle—stress, irregular sleep, lack of exposure to nature—further decreases microbial diversity and favors pathogenic bacteria.

2. Plant-Based Foods and Their Role in Restoring the Microbiome

Plant-based diets are consistently shown to support a healthier, more diverse microbiome. They provide the fibers, polyphenols, and complex carbohydrates essential for beneficial bacteria to thrive.

Key components include:

Soluble and insoluble fibers

- Soluble fibers (e.g., oats, legumes, fruits) feed SCFA-producing bacteria.

- Insoluble fibers (whole grains, vegetables) support regular bowel movements and serve as a substrate for microbial fermentation.You can learn more about fibers in my other post->

Phytonutrients and polyphenols

Polyphenols in berries, spices, herbs, teas, and colorful vegetables act as antioxidants and also function as prebiotics, shaping microbial composition toward anti-inflammatory species.

Fermented foods

Foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, miso, tempeh, and yogurt introduce beneficial microbes and metabolites. These foods enhance microbial diversity and support gut barrier function.

A plant-rich diet does not necessarily mean veganism—it simply prioritizes whole foods that nourish microbial communities and reduce inflammation.

We have to be cautious!

Although Indeed, a high number of studies and books show and present, how helpful plant-based diets are, we have to keep it into account, that people can lean towards their belief system.

Some people who personally experienced the benefits of being vegetarian, tend to write books and make contents, where they collect one-sided evidence and information.

Plant-based does not automatically mean optimal microbiome or metabolic health.

1. Ultra-processed vegan foods can harm the microbiome

Many plant-based foods today are:

- high in seed oils

- high in emulsifiers (which damage the mucosal layer)

- low in microbiota-accessible fiber

So: a vegan burger is NOT the same as whole vegetables and legumes.

Low-fiber or highly restrictive vegan diets can reduce gut diversity

If plant-based diets lack diversity or fermentable fibers, they can reduce beneficial bacteria.

Vegan ≠ high fiber by default.

Some people genetically or metabolically do poorly on high-carb plant diets

People with:

- PCOS

- insulin resistance

- NAFLD

- FTO gene variants

may experience worsened glycemia on high-carb vegan diets.

Some plants contain FODMAPs → worsen IBS symptoms

In sensitive individuals, plant foods = bloating, pain, diarrhea.

Anti-nutrients (oxalates, lectins) can irritate the gut for certain genotypes

- Spinach, beets → high oxalates

- Legumes → lectins

- Whole grains → phytates

Most people tolerate these fine.

But those with SIBO, IBD, or oxalate metabolism issues may not.

Meat provides nutrients that are harder to obtain from plants

Especially for the microbiome, nervous system, and immune function:

- B12 → supports methylation and gut motility

- Heme iron → better absorbed, supports mitochondrial function

- Taurine → supports bile acids (which regulate microbiome composition)

- Zinc → essential for intestinal barrier repair

These are BEST absorbed from meat.

3. Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Postbiotics

Prebiotics

These are non-digestible fibers that stimulate the growth of beneficial gut bacteria. Examples include inulin (chicory root), fructooligosaccharides (onions, garlic), resistant starch (cooled potatoes, green bananas), and beta-glucans (oats, mushrooms).

Probiotics

Live microorganisms that have specific health benefits. Different strains support different functions:

- Lactobacillus: supports digestion, reduces inflammation

- Bifidobacterium: improves gut barrier strength, supports SCFA production

- Saccharomyces boulardii: helps restore balance after antibiotic use

Postbiotics

These are the metabolites produced by bacteria, especially short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, acetate, and propionate.

SCFAs:

- Strengthen the gut lining

- Regulate immunity

- Influence appetite and metabolism

- Communicate with the brain via the gut–brain axis

A microbiome-friendly dietary pattern emphasizes diversity, fiber density, fermented foods, and minimal processing.

4. Gut Flora and Emotional Well-Being

The gut is often called the “second brain” because it contains the enteric nervous system—millions of neurons that communicate directly with the brain through nerves, immune signaling, and biochemical messengers.

Gut bacteria influence mood and emotional well-being by:

- Producing neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA, dopamine precursors)

- Regulating stress hormones, including cortisol

- Modulating inflammation, which affects mental clarity and mood stability

When the microbiome is imbalanced, individuals may experience:

- Anxiety

- Depressive symptoms

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Brain fog

Psychobiotic research (microbes that influence mood) suggests that certain bacterial strains can reduce cortisol levels and support emotional resilience.

The Gut–Brain Axis: How the Microbiome Affects the Nervous System

The gut–brain axis is a two-way communication system connecting the gut microbiome, the immune system, and the brain.

Vagus nerve

This major nerve acts as a communication highway. Beneficial microbes produce metabolites that activate vagal pathways, promoting relaxation and reducing stress responses.

Inflammation & neuroinflammation

A compromised gut barrier allows endotoxins to enter the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation that can influence the brain. Chronic, low-grade inflammation is implicated in anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation, and even neurodegenerative diseases.

Gut permeability

“Leaky gut” increases immune activation, which may alter neurotransmitter production and brain function.

Microbiome → Immune System → Brain

Around 70% of the immune system resides in the gut. Microbial metabolites regulate immune cells, which in turn influence neuroinflammation and brain health. This three-way relationship highlights why gut health is essential for cognitive and emotional well-being.

Balanced conclusion (supported by research)

✔ Plant-based diets can be extremely healthy

BUT only when they are diverse, rich in whole foods, and not ultra-processed.

✔ Meat is NOT inherently harmful

Unprocessed, high-quality meat can fit well into a healthy, microbiome-supportive diet.

✔ The microbiome thrives on variety

→ fiber + polyphenols

→ enough protein

→ low processed food

→ healthy fats

✔ The “best diet” is individual

The research overwhelmingly shows:

👉 Genes

👉 gut type

👉 metabolic status

👉 lifestyle

all affect what diet works best.

Resources

Dr. Szentgyörgyi Barbara – Azt tényleg megeszed?

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24336217/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22121108/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1552366/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30588210/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28675945/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4474417/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30081136/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18043614/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31536878/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28464483/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4898365/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31374082/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25365383/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31058160/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32981834/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772753X23002472

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25402818/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21710560/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33529749/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24192538/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34527688/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38965727/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27568549/

https://2024.sci-hub.st/7787/88268e9c25c8b7e95dc7cd9c91e93143/lavefve2019.pdf

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31100380/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26255043/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31145873/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17078771/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28405151/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17101300/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23544058/

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)60360-1/abstract

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25689247/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22638926/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25860609/

https://archive.org/details/secondbrainscien00gers

https://bookline.hu/szerzo/giulia-enders/12812710?page=1

https://bookline.hu/product/home.action?_v=Mayer_Emeran_A_bel_agy_kapcsolat&type=22&id=346083

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36760344/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39394665/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24393738/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24076059/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12389504/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8308632/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4910713/